Every year, Americans spend over $600 billion on prescription drugs. About 90% of those prescriptions are for generics - cheap, safe, and just as effective as brand-name drugs. But here’s the twist: even though generics cost 80% less, many patients still get the brand version. Why? Because the system doesn’t always push them toward the cheaper option. That’s where state-level generic prescribing incentives come in.

How States Are Pushing Doctors and Pharmacies Toward Generics

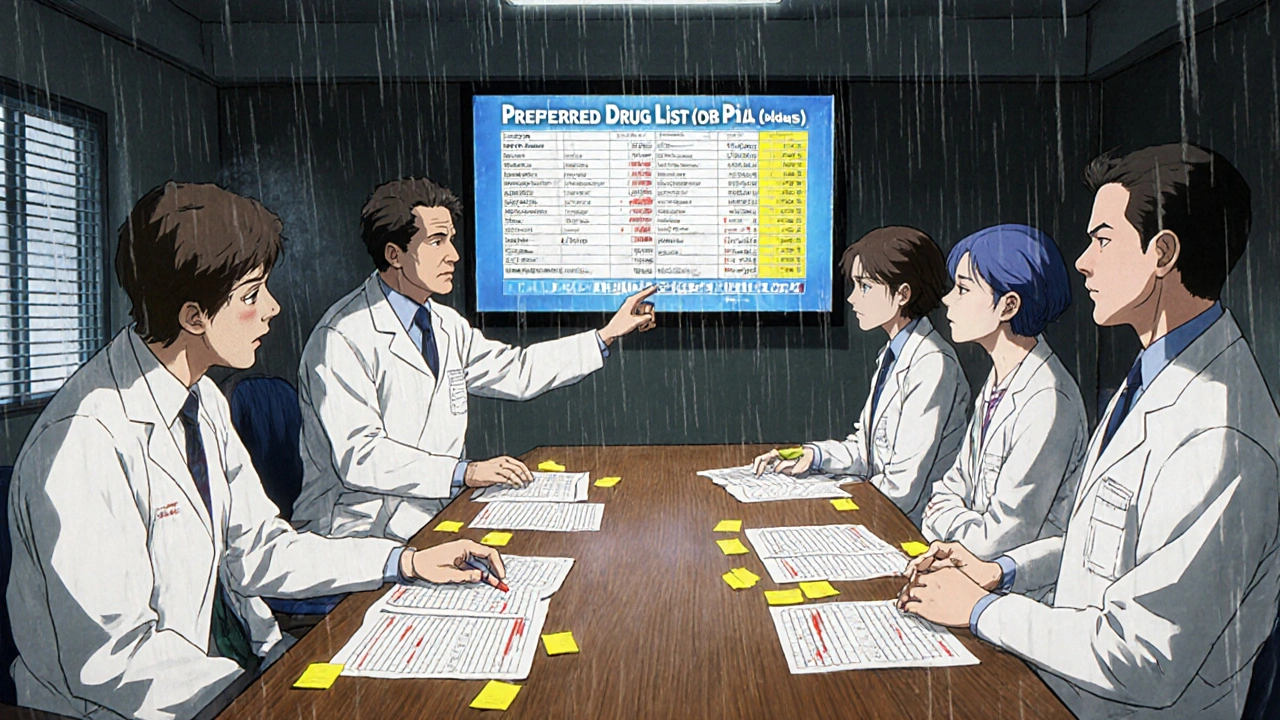

States aren’t waiting for federal action. They’ve built their own systems to nudge prescribers, pharmacists, and patients toward generics. The most common tool? Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs). These are lists of drugs that Medicaid will cover with the lowest out-of-pocket cost. If a doctor prescribes a drug not on the list, the patient pays more - or the doctor has to jump through hoops to get approval. As of 2019, 46 out of 50 states used PDLs for their Medicaid programs. In 29 of those states, a committee of doctors and pharmacists - called a Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee - decides which drugs make the list. The rest rely on Medicaid agencies or drug review boards. These lists aren’t static. Twenty states review them every year. Ten do it quarterly. That means the list can change fast if a new generic hits the market or a brand-name drug drops its price.The Real Power Move: Presumed Consent Laws

Here’s where it gets interesting. Some states let pharmacists swap a brand-name drug for a generic without asking the patient first. That’s called presumed consent. Other states require the pharmacist to ask the patient for permission - explicit consent. A 2018 NIH study found a clear winner: presumed consent. States with presumed consent laws saw a 3.2 percentage point increase in generic dispensing compared to those that required patient permission. That might not sound like much, but it adds up. If all 39 explicit consent states switched to presumed consent, they could save $51 billion a year in drug spending. And here’s the kicker: mandatory substitution laws - where pharmacists are legally required to substitute - didn’t move the needle. Why? Because pharmacists already make more money dispensing generics. They don’t need a law to tell them to do it. But patients? They need a nudge. Presumed consent works because it removes the friction. No extra questions. No extra time. Just the cheaper, equally good option.Copay Differentials: Putting the Cost in the Patient’s Hands

States also use copay differentials to steer behavior. If a brand-name drug costs $30 and the generic costs $5, the patient pays $10 for the brand and $5 for the generic. That $5 difference isn’t just a savings - it’s a signal. In 2000, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that the gap between brand and generic copays had widened significantly since the 1990s, even as the profit margin for pharmacies on generics shrank to just 8 cents per prescription. That means pharmacies weren’t making more money off generics - patients were being directly incentivized to choose them. The Department of Health and Human Services confirmed this approach works better than trying to pay pharmacists more to dispense generics. Incentives aimed at patients - not providers - get results. That’s why states have moved away from paying pharmacists bonuses and toward raising copays for brand-name drugs.

The Hidden Problem: When Generics Disappear

It sounds simple: reward generics, save money. But there’s a dark side. The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program requires drugmakers to pay rebates to states based on the drug’s price. For generics, that’s usually a 13% base rebate. But states can negotiate extra rebates on top of that. Here’s the trap: if a generic drug’s price drops because of market competition, the rebate amount doesn’t drop with it. It’s still calculated based on the original price. That means a manufacturer could end up paying more in rebates than they make from selling the drug. That’s not sustainable. Avalere Health found five scenarios where this happens - like when a drug’s ingredient costs go up but the selling price doesn’t, or when a generic becomes so common that prices crash. In those cases, manufacturers pull the drug from Medicaid entirely. No more supply. No more savings. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happened. In some states, patients who relied on a low-cost generic suddenly found it unavailable. The system worked too well - and broke the market.The 340B Program: A Parallel Incentive

While states focus on Medicaid, another program quietly boosts generic use: the 340B Drug Pricing Program. Created in 1992, it lets safety-net hospitals, clinics, and community health centers buy drugs at deeply discounted prices - often 20% to 50% off. These entities - which serve low-income patients - are major buyers of generics. The program doesn’t force substitution, but it makes generics so cheap that clinics naturally choose them. In 2016, CMS ruled that states must reimburse 340B drugs based on their actual acquisition cost, not a fixed rate. That meant states had to track real prices, not guess them. It added complexity, but it also ensured clinics weren’t overpaid - and kept using affordable drugs.What’s Next? The $2 Drug List

The federal government is watching. CMS is testing a new model called the $2 Drug List. It’s simple: for a handful of the cheapest, most common generics, Medicare Part D beneficiaries pay just $2 per prescription - no matter the brand. It’s not mandatory. States can’t force it. But if it works, it could become a blueprint. Imagine if every state adopted a version of this - a short list of generics priced at $2, $5, or $10. No copay tiers. No prior auth. Just clear, simple savings. Some states are already experimenting. Others are waiting to see if it cuts costs without causing shortages. The big question isn’t whether it works - it’s whether the generic market can handle it. If too many drugs get priced too low, manufacturers might leave. That’s the tightrope states walk: save money today without killing the supply tomorrow.

Why This Matters to You

If you’re on Medicaid, Medicare, or even private insurance with a formulary, these policies affect your pocketbook. You might not know it, but the drug you get - and how much you pay - is shaped by decisions made in state capitals, not just your doctor’s office. The goal isn’t to ban brand-name drugs. It’s to make sure you get the best value. A generic isn’t a second-choice drug. It’s the same medicine, made by the same company, under the same rules - just without the marketing budget. When states get this right, patients get cheaper meds. Pharmacies get steady business. Taxpayers get relief. And the system doesn’t collapse. But when they push too hard - when rebates become punitive, or when lists change too fast - the system backfires. The trick is balance. Not control. Not coercion. Just smart incentives.What You Can Do

You don’t need to understand Medicaid rebates or PDLs to make a difference. Here’s what you can do today:- Ask your pharmacist: "Is there a generic version?" Always.

- If your copay is high, ask if your insurance has a lower tier for generics.

- If a drug you need disappears, contact your state Medicaid office or patient advocacy group. You’re not alone.

- Don’t assume brand = better. Generics are tested to be just as effective.

What are generic prescribing incentives?

Generic prescribing incentives are state-level policies that encourage doctors, pharmacists, and patients to choose generic drugs over brand-name ones. These include higher copays for brand drugs, preferred drug lists (PDLs), and laws that let pharmacists substitute generics without asking the patient first (presumed consent).

Do generic drugs work the same as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They must also be bioequivalent - meaning they work the same way in the body. The only differences are in inactive ingredients, packaging, and price.

Why do some states require patient consent before substituting generics?

Some states believe patients should have the final say, especially if they’ve had a bad reaction to a generic in the past. But research shows this slows down substitution. States with presumed consent - where substitution happens automatically - see higher generic use rates without compromising safety.

Can generic drugs disappear from the market?

Yes. If a generic manufacturer loses money because of Medicaid rebate rules - like when drug prices drop but rebates stay high - they may stop making the drug. This has happened in several states, leaving patients without access to affordable versions of essential medications.

What is the $2 Drug List and how does it affect states?

The $2 Drug List is a federal Medicare Part D pilot program that caps the cost of select low-cost generics at $2 per prescription. It’s voluntary for states, but if it proves successful, it could become a model for state Medicaid programs - simplifying cost-sharing and encouraging generic use without complex formularies.

How do Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs) work?

PDLs are lists of drugs that Medicaid will cover with the lowest patient cost. If a doctor prescribes a drug not on the list, the patient pays more - or the prescriber must get prior authorization. These lists are updated regularly and are managed by pharmacy and therapeutics committees in most states.

Do pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) play a role in generic incentives?

Yes. PBMs often design formularies and negotiate rebates with drugmakers. Some offer pharmacies higher dispensing fees for generics or penalize them for dispensing brand drugs when generics are available. But studies show these provider-focused incentives are less effective than direct patient copay differentials.

vanessa k

November 12, 2025 at 00:08

So let me get this straight - we’re paying $30 for a brand-name pill when the generic does the exact same thing for $5, and the system still makes us jump through hoops? This isn’t healthcare, it’s a rigged casino. I’ve had my insulin switched without warning and ended up in the ER because the generic was ‘different.’ No, it wasn’t. It was just cheaper. And now I don’t trust any of it.