By early 2026, the U.S. and global drug supply chains are still reeling from a perfect storm: rising raw material costs, geopolitical disruptions, and unrelenting pricing pressure from insurers and government programs. The result? Drug shortages are no longer rare events-they’re systemic. And behind every empty shelf in a pharmacy is a manufacturer caught between losing money or losing customers.

It’s not just about running out of pills. It’s about who can afford to make them. Generic drug makers, who produce over 90% of the medications Americans take, are being squeezed harder than ever. Their profit margins have collapsed. Input costs for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) have jumped 18% since 2023, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s 2025 Supply Chain Report. At the same time, Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates haven’t increased in over five years. Many manufacturers now lose money on every bottle they produce-yet they’re forced to keep making them to stay in business.

Take insulin, for example. In 2025, four companies controlled 98% of the U.S. market. Three of them reported net margins below 5%-down from 12% in 2020. Why? Because while the cost of insulin’s key raw materials rose by 22%, the government capped what pharmacies could charge patients at $35 per prescription. The manufacturers didn’t get to raise prices. They didn’t get subsidies. They just got fewer orders.

And then there’s the supply chain. Over 80% of APIs used in U.S. drugs come from India and China. Trade restrictions, port delays, and environmental crackdowns in those countries have made it harder to get consistent shipments. In 2024, a single factory shutdown in Gujarat, India, caused a nationwide shortage of metformin-the most common diabetes drug. It took nine months to recover. During that time, hospitals scrambled for alternatives. Some patients went without.

It’s not just big-name drugs. Even simple antibiotics like amoxicillin and doxycycline have seen multiple shortages since 2023. Why? Because they’re cheap to buy but expensive to make. The cost of packaging, labor, quality testing, and regulatory compliance has outpaced the price these drugs can sell for. One midsize U.S. manufacturer told the FDA in a confidential 2025 survey that they lost $1.2 million on amoxicillin last year-yet they kept producing it because stopping would mean losing their license to operate.

The financial strain isn’t theoretical. A 2025 survey of 127 generic drug producers by the Generic Pharmaceutical Association found that 68% had cut R&D budgets, 54% delayed equipment upgrades, and 41% reduced workforce size. Many are now operating with just enough staff to meet minimum production quotas. No room for error. No buffer for disruption.

Some manufacturers have tried to adapt. A few have moved production to Mexico or Eastern Europe, hoping to dodge tariffs and reduce shipping delays. Others have invested in vertical integration-buying their own API plants in countries like Vietnam and Romania. But these moves cost millions. And they take years. Meanwhile, the shortages keep coming.

Insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) aren’t helping. They demand the lowest possible price, then punish manufacturers for not meeting unrealistic volume targets. One manufacturer in Ohio reported being fined $450,000 in 2025 for failing to deliver 500,000 units of a generic blood pressure drug-even though a port strike delayed their shipment by three weeks. They still had to pay the fine. They still had to pay their workers. They still had to pay for the raw materials that sat in storage, degrading.

And here’s the cruel twist: when shortages hit, prices spike. Not for the manufacturer-but for the patient. Pharmacies, desperate to restock, turn to secondary distributors who charge 300-500% more. A 30-day supply of levothyroxine that normally costs $12 suddenly jumps to $48. Patients skip doses. Some stop taking it altogether. The health consequences are real. Hospitalizations rise. Emergency room visits climb. The system breaks down one pill at a time.

There are signs of change. The FDA has started publishing real-time shortage alerts and fast-tracking approvals for new suppliers. In 2025, they approved five new generic manufacturers for drugs that had been in short supply for over two years. One of them, a small Canadian firm, now supplies 15% of the U.S. market for clonazepam-after investing $18 million in U.S.-based quality control labs.

Some states are stepping in too. California passed a law in 2025 requiring PBMs to disclose their pricing margins. New York created a state-run drug procurement program to buy generics in bulk and distribute them to public hospitals at cost. These are small steps-but they’re steps in the right direction.

What’s missing? A real plan. No one is paying manufacturers to make the drugs we need. No one is guaranteeing them stable prices. No one is helping them build resilient supply chains. Until then, the cycle will continue: manufacturers lose money → cut production → shortages happen → prices spike → patients suffer → manufacturers lose more money.

The solution isn’t just about fixing supply chains. It’s about fixing the economics. If we want drugs to be available, we have to make sure making them isn’t a financial suicide mission.

Why Generic Drug Manufacturers Can’t Raise Prices

It’s easy to assume that if drug makers are losing money, they should just raise prices. But that’s not how the system works. Generic drugs are sold in a hyper-competitive market where every pharmacy, hospital, and insurer is hunting for the lowest bid.

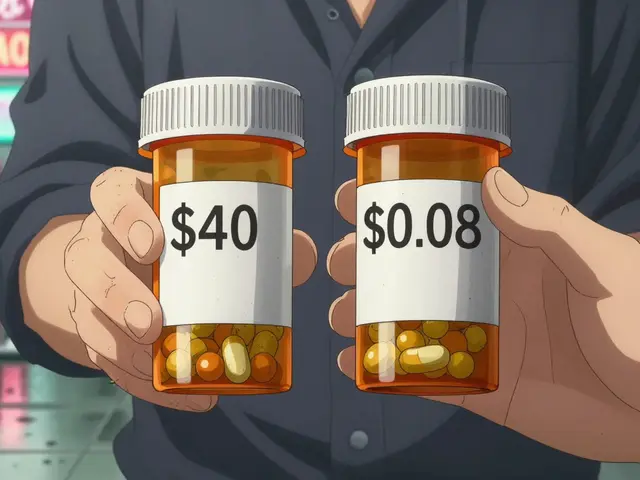

When a generic drug loses patent protection, dozens of companies jump in to make it. The price drops fast-sometimes by 90% in the first year. Once it’s down to pennies per pill, manufacturers compete on volume, not profit. If one company raises its price even slightly, buyers switch to the next cheapest supplier.

Medicare Part D and Medicaid are major buyers. They use formularies to steer patients toward the cheapest options. If your drug isn’t the lowest price, you’re off the list. That means even if your costs go up, you can’t raise your price without losing 80% of your customers.

One manufacturer in North Carolina told the FDA they had to drop their price for furosemide (a common diuretic) from $0.18 to $0.07 per tablet in 2024. Their cost to make it? $0.09. They’re losing two cents per tablet. But they keep making it because they need the volume to cover overhead. If they stop, they risk losing their manufacturing license-and with it, their ability to make any drugs at all.

The Role of Tariffs and Global Trade Disruptions

Since 2023, tariffs on pharmaceutical inputs from China and India have increased by 15-20%. These aren’t on finished drugs-they’re on the chemicals and materials used to make them. Raw materials like benzene, acetone, and rare catalysts now cost more to import. Some of these are essential for producing antibiotics, antivirals, and heart medications.

Between 2023 and 2025, the cost of importing APIs rose 22% on average. The FDA estimates that 30% of recent drug shortages were directly linked to tariff delays or supply disruptions from Asia. One manufacturer in Pennsylvania said they lost $3.1 million in 2024 because a shipment of API for a generic antidepressant was held up at a U.S. port for 47 days due to customs inspections. The material expired before it could be used. They couldn’t claim insurance. They couldn’t get a replacement in time.

Some companies are trying to shift production to Mexico, where tariffs are lower and shipping times are faster. But that requires new regulatory approvals, new equipment, and new staff. It takes 18-24 months. And even then, you’re not out of the woods-Mexico still imports many of its own APIs from Asia.

How Shortages Hurt Patients-and the System

When a drug is in short supply, patients don’t just wait. They suffer.

Diabetic patients miss insulin doses. Cancer patients delay chemotherapy. Heart patients switch to less effective alternatives. A 2025 study in The New England Journal of Medicine found that patients who experienced a drug shortage were 34% more likely to be hospitalized in the following six months.

And it’s not just about health. It’s about cost. When a generic drug disappears, the alternative is often a brand-name version-priced at 10x more. A patient on a fixed income may choose to skip the drug entirely. That leads to complications. More doctor visits. More ER trips. More taxpayer money spent on emergency care.

Pharmacies, caught in the middle, often charge patients the full cash price-even if their insurance should cover it. Some patients get billed $200 for a drug that normally costs $15. They’re angry. Confused. And they lose trust in the system.

What’s Being Done-and Why It’s Not Enough

The FDA has created a Drug Shortage Task Force. They now require manufacturers to give six months’ notice before stopping production. They’ve fast-tracked approvals for new suppliers. In 2025, they approved 17 new generic drug applications, the highest number in a decade.

But notice requirements don’t help if a factory burns down or a shipment is seized. Fast-tracking doesn’t help if there’s no one with the capacity to build the plant.

Some lawmakers have proposed the Drug Supply Chain Security Act, which would give the government authority to stockpile critical drugs and subsidize domestic production. But the bill has stalled in Congress. Without funding, it’s just words.

Meanwhile, manufacturers are left to fend for themselves. Many are cutting corners-reducing quality control, skipping maintenance, delaying audits. That’s dangerous. And it’s happening more often.

What Needs to Change

Here’s what actually works:

- Guaranteed minimum prices for essential generic drugs-enough to cover cost plus a small, fair profit.

- Domestic production incentives-tax credits, grants, and low-interest loans for companies building API facilities in the U.S.

- Strategic stockpiles-government reserves of critical drugs that can be released during shortages.

- Transparent pricing data-so manufacturers know what they’re competing against.

- One-time funding to help small manufacturers upgrade equipment and meet new safety standards.

None of these are expensive compared to the cost of hospitalizations, lost productivity, and preventable deaths. But they require political will. And right now, that’s in short supply.

What Patients Can Do

While systemic change is slow, patients aren’t powerless:

- Check the FDA’s Drug Shortage Database regularly. It’s updated weekly.

- Ask your pharmacist if there’s an alternative. Sometimes a different brand or formulation works just as well.

- Call your insurance company. If your drug is unavailable, they may cover a more expensive version temporarily.

- Join patient advocacy groups. Collective pressure moves policy.

Don’t assume the system will fix itself. It won’t. But if enough people speak up, change can happen.

Ryan Riesterer

January 23, 2026 at 09:49

The structural inefficiencies in the generic drug supply chain are a classic case of market failure exacerbated by regulatory capture. The current reimbursement model, anchored in 2019-era cost benchmarks, fails to account for inflation-adjusted API expenditures, logistics volatility, and compliance overhead. Manufacturers are trapped in a prisoner’s dilemma: produce at a loss or exit the market entirely. Without a cost-plus pricing mechanism tied to tiered essentiality metrics, this cycle is self-reinforcing.

Further, the FDA’s six-month notice requirement is functionally useless when disruptions are exogenous - fire, port strikes, geopolitical sanctions - not endogenous production decisions. Real-time supply chain visibility and dynamic buffer stock protocols are needed, not bureaucratic notifications.

Vertical integration into Vietnam and Romania is a tactical workaround, but it doesn’t resolve the core issue: the U.S. has outsourced its pharmaceutical sovereignty to jurisdictions with weaker regulatory enforcement and higher geopolitical risk.

The 2025 Generic Pharmaceutical Association survey data confirms systemic underinvestment in CAPEX. Without federal grants or tax credits to modernize GMP facilities, we’re gambling with public health on obsolete equipment.

And let’s not forget: PBMs are extractive intermediaries. Their opaque rebate structures incentivize volume over value, rewarding the cheapest bidder regardless of reliability. Transparency mandates are a start, but we need structural separation between pharmacy benefit management and drug procurement.

The NEJM study on hospitalization spikes is damning. This isn’t a supply issue - it’s a moral hazard problem. We’ve commodified life-saving medication to the point where profit margins dictate access.

There’s no technical barrier to fixing this. Only political will. And that’s in short supply.

Canada’s clonazepam example proves it’s possible: state-backed investment in quality infrastructure, paired with guaranteed volume commitments, yields resilience. Why isn’t that the U.S. model?