Chemical Waste: Risks, Regulations, and How Medications Contribute to Environmental Harm

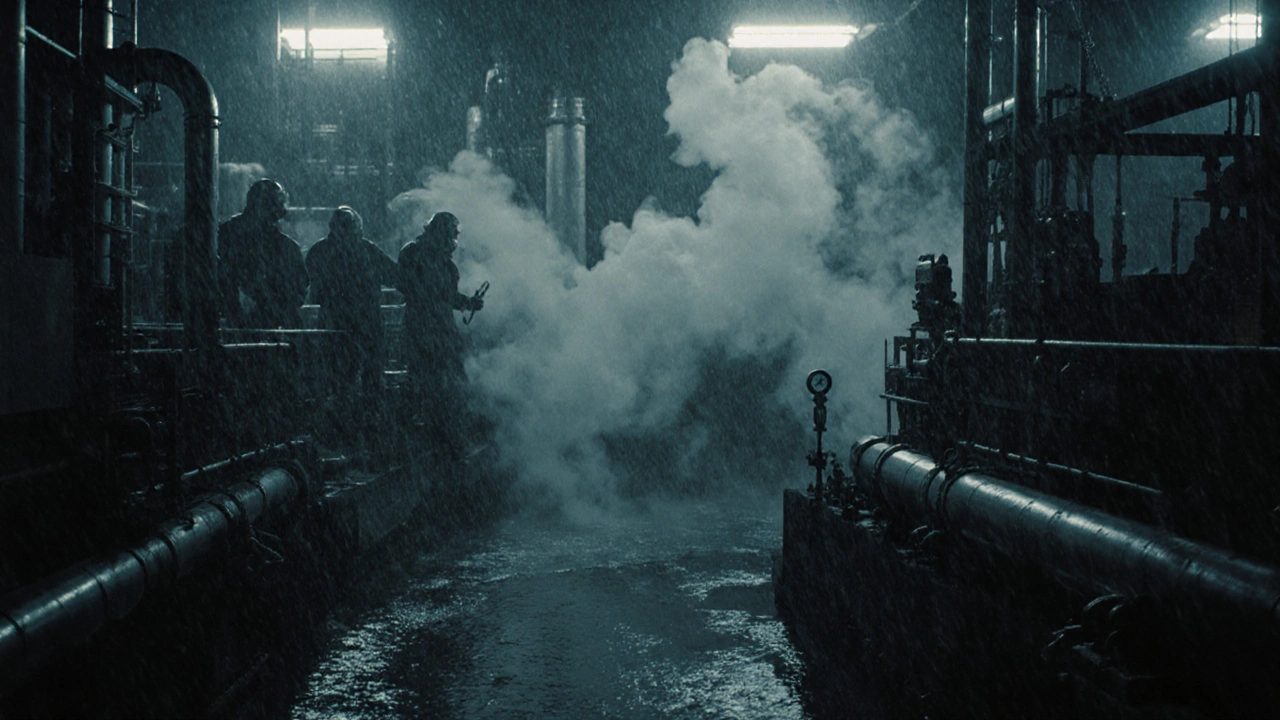

When you flush an old pill or toss expired medicine in the trash, you’re adding to a growing problem: chemical waste, toxic byproducts from manufacturing, use, and disposal of pharmaceuticals and other chemicals. Also known as pharmaceutical waste, this type of contamination shows up in rivers, drinking water, and even fish tissue—often at levels too low to notice but high enough to cause long-term harm. It’s not just industrial plants dumping toxins. A huge part comes from everyday medicine use: leftover antibiotics, unused painkillers, and outdated antidepressants that end up in landfills or flushed down toilets.

Pharmaceutical waste, unused or expired drugs that enter the environment through improper disposal is especially tricky because these substances are designed to be biologically active. Even tiny amounts of hormones, antibiotics, or chemotherapy drugs can disrupt fish reproduction, trigger antibiotic resistance in bacteria, or alter aquatic ecosystems. The drug disposal, the process of safely discarding medications to prevent environmental and public health risks methods most people use—throwing pills in the trash or flushing them—are outdated and dangerous. The FDA and EPA have pushed for take-back programs, but only a fraction of communities offer them. Meanwhile, environmental contamination, the presence of harmful substances in air, water, or soil due to human activity from pharmaceuticals is rising, with studies finding over 60 different drugs in U.S. water supplies.

What makes this worse is that most wastewater treatment plants aren’t built to remove complex drug molecules. They filter out solids and kill bacteria, but they can’t catch something like carbamazepine or estradiol. These chemicals pass through, end up in rivers, and get reused downstream. And while regulators focus on big manufacturers, the real volume comes from households. Every bottle of antibiotics you don’t finish, every patch you throw away, every bottle of insulin you no longer need—it all adds up. There’s no single fix, but awareness helps. Knowing how to properly dispose of meds, supporting take-back programs, and asking your pharmacy about safe disposal options can make a real difference.

Behind every recall of contaminated generics, every alert about nitrosamines in blood pressure meds, and every story about antibiotic-resistant infections, there’s a chain of waste and mismanagement. The same systems that deliver life-saving drugs also create dangerous byproducts. This collection of articles doesn’t just explain how medications work—it shows how they interact with the world after you’re done with them. You’ll find guides on safe disposal, reports on pollution from generic drug production, and insights into how pharmacy practices affect the environment. Whether you’re a patient, a caregiver, or just someone who cares about clean water, this isn’t just about medicine. It’s about what happens when medicine doesn’t stop at the bottle.

The Environmental Impact of Eflornithine Production

Eflornithine saves lives from sleeping sickness, but its chemical production generates toxic waste and high emissions. A greener method exists - but isn't being used. Here's why.

About

Medications

Latest Posts

Rasagiline’s Role in Slowing Parkinson’s Disease Progression

By Orion Kingsworth Oct 21, 2025

Buy Cheap Generic Synthroid Online - Safe, Fast & Affordable

By Orion Kingsworth Oct 13, 2025

10 Alternatives to Losartan: A Straightforward Guide to Hypertension Options

By Orion Kingsworth Apr 15, 2025