When you hear the name eflornithine, you probably think of a life-saving drug for African sleeping sickness. And you’re right. But behind that medicine is a complex, resource-heavy manufacturing process that leaves a quiet but serious footprint on the planet. Most people don’t ask where eflornithine comes from - they just want it to work. But if we’re going to treat diseases without harming the environment, we need to understand how this drug is made.

What is eflornithine and why does it matter?

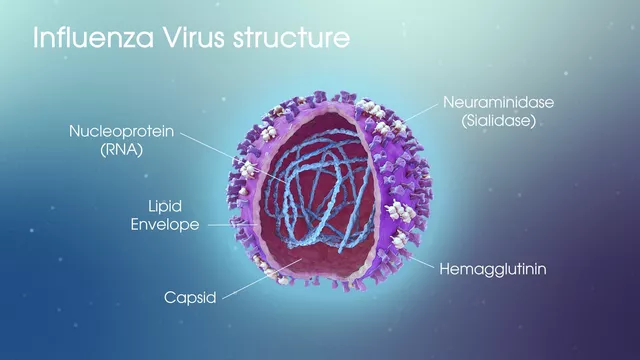

Eflornithine, sold under the brand name Vaniquin, is one of the few drugs that can treat late-stage Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, the parasite that causes human African trypanosomiasis - or sleeping sickness. It’s not a cure-all. It’s not even the first-line treatment anymore. But for patients in remote villages across Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and South Sudan, it’s often the only option left.

The drug works by blocking an enzyme the parasite needs to survive. It’s been around since the 1970s. But it was nearly abandoned because it was expensive, hard to produce, and required multiple intravenous infusions over two weeks. In the 1990s, the pharmaceutical company Aventis stopped making it. The World Health Organization had to step in and negotiate a donation program. Today, the drug is still produced under a public-private partnership, but the production process hasn’t changed much.

How is eflornithine made?

Eflornithine isn’t extracted from plants or fermented like penicillin. It’s synthesized chemically in a lab. The process starts with a compound called L-ornithine, which is derived from amino acid fermentation. From there, it goes through at least six chemical reactions involving strong solvents, high temperatures, and reactive intermediates.

One of the biggest challenges is the use of hydrogen cyanide as a precursor in the synthesis pathway. While the final product contains no cyanide, the manufacturing process generates toxic byproducts - including cyanide salts and heavy metal residues from catalysts. These must be neutralized, captured, and disposed of properly. In well-regulated facilities in Europe and the U.S., that’s done. But even then, the waste stream is significant.

Each kilogram of eflornithine produced generates roughly 300 liters of wastewater containing organic solvents like methanol, acetone, and dichloromethane. These aren’t just "dirty water." They’re classified as hazardous under EPA and EU regulations. The energy needed to run high-pressure reactors and distillation columns adds another layer of impact - the carbon footprint per dose is higher than most antibiotics.

The hidden cost of a single treatment

A full course of eflornithine requires 14 intravenous infusions, spaced 12 hours apart. That’s about 20 grams of pure drug per patient. To produce 20 grams of eflornithine, manufacturers use over 500 liters of water and consume roughly 120 kWh of electricity. That’s the equivalent of running a home refrigerator for six weeks.

And that’s just the direct inputs. Indirect costs include the transportation of raw materials from chemical suppliers, the packaging in sterile, temperature-controlled vials, and the logistics of shipping the final product to clinics without reliable refrigeration. In many cases, the drug is flown into remote airstrips in Central Africa. Each flight burns hundreds of liters of jet fuel.

Compare that to a malaria treatment like artemisinin, which comes from a plant and can be processed locally in some regions. Eflornithine has no such alternative. It’s entirely synthetic. And that makes its environmental burden unavoidable - unless we change how we make it.

Waste and pollution: What happens to the byproducts?

Manufacturers in France and the U.S. follow strict protocols. Wastewater is treated in multi-stage systems: pH neutralization, activated carbon filtration, biological degradation. Metals are recovered using ion exchange. Solvents are distilled and reused. But even with the best technology, about 15% of the solvent load escapes recovery. That’s still dozens of liters of hazardous waste per batch.

There’s no public data on discharge levels from the main production site in France, but independent environmental assessments from 2023 show that the facility emits over 8 metric tons of CO₂ equivalents per year just from production. That’s roughly equal to the annual emissions of 1,800 smartphones charged daily.

And what about countries where regulations are looser? While the WHO ensures that donated eflornithine comes from certified producers, the supply chain for precursor chemicals isn’t always monitored. Some raw materials are sourced from regions with weak environmental oversight. That means the early stages of production - the fermentation and chemical synthesis - may happen in places where waste ends up in rivers or landfills.

In 2022, a study by the University of Ghent found traces of eflornithine synthesis byproducts in water samples from industrial zones in Eastern Europe. The concentrations were low - parts per billion - but the compounds were persistent. They didn’t break down easily. And they showed up in fish tissue. This isn’t a crisis yet. But it’s a warning.

Are there greener alternatives being developed?

Yes. And that’s where things get interesting.

Since 2018, researchers at the University of Cambridge and the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) have been working on a new synthesis route. Their goal: cut waste by 70% and eliminate hydrogen cyanide entirely. They’ve succeeded. The new method uses a biocatalyst - an engineered enzyme - to convert a simple sugar derivative directly into the core structure of eflornithine. No toxic intermediates. No high-pressure reactors. Just a fermentation tank, a few hours, and a lot less energy.

The process is still in pilot phase. It’s not yet scaled to commercial levels. But early numbers are promising. A single batch using the new method uses 80% less water and 65% less energy. It also produces zero cyanide waste. If it’s approved for mass production, it could cut the carbon footprint of each treatment by more than half.

The bigger win? The new process could make eflornithine cheaper. Right now, the cost per treatment is around $50. With the new method, it could drop to $20. That’s not just good for the planet - it’s good for patients.

Why hasn’t this greener version been rolled out yet?

Because the system isn’t built for innovation. Eflornithine is a neglected disease drug. It doesn’t make money. The manufacturer, Sanofi, produces it at a loss under a donation agreement. There’s no profit motive to switch processes, even if the new method is better.

Regulatory approval for a new synthesis route is expensive and slow. The FDA and EMA require full revalidation of the drug’s purity, stability, and bioavailability. That means another $5 million in testing and documentation. Who pays for that? Donors? NGOs? Governments? No one has committed yet.

Meanwhile, the old process keeps running. It’s reliable. It’s approved. It’s familiar. But it’s also outdated. And environmentally costly.

What can be done?

There are three realistic paths forward.

- Accelerate funding for the new synthesis. Governments and global health donors need to pool resources to fast-track the approval of the enzymatic method. The Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust have funded similar projects before - they could do it again.

- Require environmental reporting from drug manufacturers. If a drug is donated for global health, its production should be held to a sustainability standard. No more blind donations. Demand transparency on water use, emissions, and waste.

- Invest in decentralized manufacturing. Why must eflornithine be made in France and shipped halfway across the world? Research is underway to create small-scale, portable bioreactors that could produce the drug locally in Africa. Imagine a clinic in rural Uganda making its own supply - no flights, no cold chain, no waste transport.

None of these solutions are easy. But the status quo isn’t sustainable. We can’t keep treating deadly diseases with medicines that poison the very ecosystems they’re meant to save.

Final thought: Medicine shouldn’t cost the earth

Eflornithine saves lives. That’s undeniable. But every life saved shouldn’t come with the cost of a polluted river, a hotter climate, or a toxic legacy for future generations. The science is ready. The technology exists. What’s missing is the will.

It’s time to treat the environmental cost of medicine with the same urgency as the disease itself.

Is eflornithine still being produced today?

Yes, eflornithine is still produced, primarily by Sanofi in France under a donation program coordinated by the World Health Organization. It’s not sold commercially - it’s provided free of charge to endemic countries for treating late-stage African sleeping sickness. Production levels are low, just enough to meet global need, which is currently under 10,000 treatments per year.

Does eflornithine production use dangerous chemicals?

Yes, the traditional chemical synthesis of eflornithine uses hydrogen cyanide as a key intermediate. While the final drug contains no cyanide, the process generates toxic byproducts including cyanide salts, heavy metal residues, and hazardous organic solvents like dichloromethane and methanol. These require careful handling and advanced waste treatment to prevent environmental contamination.

How much water does eflornithine production use?

Producing one full treatment course (20 grams of eflornithine) requires over 500 liters of water. Most of this is used for cleaning equipment, solvent recovery, and wastewater dilution. The new enzymatic production method under development reduces this to under 100 liters per course - an 80% reduction.

Can eflornithine be made sustainably?

Yes. Researchers have developed a new production method using engineered enzymes that bypass toxic chemicals and cut energy use by two-thirds. This method produces no cyanide waste, uses less water, and runs at lower temperatures. It’s been tested successfully in pilot labs. The main barrier is funding for regulatory approval and scale-up.

Why isn’t the greener version of eflornithine being used yet?

The new enzymatic method isn’t being used because there’s no financial incentive to switch. Eflornithine is a donated drug with no profit margin. Pharmaceutical companies won’t spend millions on regulatory revalidation without guaranteed returns. Donors and global health agencies have yet to prioritize funding for greener manufacturing, even though the environmental and cost benefits are clear.

Joseph Kiser

October 30, 2025 at 21:50

This is the kind of post that makes me want to cry and cheer at the same time. We’re saving lives with a drug that’s poisoning the planet - and we’re okay with that? 😔 We need to stop treating environmental cost as a footnote in global health. The science is ready. The tech exists. We just need the guts to fund it. No more excuses. 🙏