Environmental Impact of Pharmaceuticals: How Medications Affect Water, Soil, and Wildlife

When you flush old pills or toss expired meds in the trash, you’re not just cleaning out your medicine cabinet—you’re adding to a growing environmental impact, the unintended harm caused by pharmaceuticals entering ecosystems through improper disposal and human excretion. Also known as pharmaceutical pollution, this issue affects rivers, lakes, and even drinking water supplies worldwide. It’s not just about pills you don’t need. Antibiotics, antidepressants, hormones, and painkillers are showing up in fish, frogs, and birds, changing their behavior, reproduction, and survival rates. The U.S. Geological Survey found traces of over 80 different drugs in streams across 30 states. These aren’t random chemicals—they’re active ingredients designed to change how your body works, and they don’t just disappear after you use them.

The biggest source? Human waste. When you take a pill, your body doesn’t absorb everything. Unmetabolized drugs pass through you and enter sewage systems. Most wastewater plants aren’t built to remove complex pharmaceutical compounds, so they end up in rivers and lakes. Then there’s improper disposal: flushing medications, throwing pills in the trash where they can leach into groundwater, or hoarding old drugs until they’re forgotten. pharmaceutical waste, unused or expired medications that enter the environment through disposal or runoff is a silent crisis. In places where people dump leftover antibiotics, it’s not just pollution—it’s fueling drug-resistant bacteria. antibiotic pollution, the release of antibiotics into ecosystems that promotes resistant microbial strains is one of the fastest-growing public health threats, even before you get sick.

It’s not just about the drugs themselves. The packaging matters too. Plastic blister packs, glass bottles, and foil wrappers from medications end up in landfills and oceans. Recycling them is rarely an option because of contamination risks. And while regulators focus on drug safety for people, the environment often gets left out of the equation. That’s why some states now offer take-back programs, and why pharmacies are starting to collect old meds. But most people still don’t know where to drop them off—or think it’s fine to flush them because ‘the system will handle it.’ It won’t. The water contamination, the presence of pharmaceutical residues in drinking water and aquatic environments is real, measurable, and getting worse.

What you can do is simple: never flush anything unless the label says to. Don’t throw meds in the trash without mixing them with coffee grounds or kitty litter first. Check if your pharmacy or local government runs a drug take-back day. And if you’re on long-term meds, ask your doctor if you can get smaller prescriptions to avoid leftovers. These steps won’t fix the whole problem—but they stop you from making it worse. Below, you’ll find real stories and data from people who’ve seen the effects firsthand: from antibiotic-resistant infections tied to polluted water, to how improper disposal of Cefprozil or nitrosamine-contaminated generics adds to the problem. This isn’t theory. It’s happening in your backyard, your river, your tap water. And you have more power to change it than you think.

The Environmental Impact of Eflornithine Production

Eflornithine saves lives from sleeping sickness, but its chemical production generates toxic waste and high emissions. A greener method exists - but isn't being used. Here's why.

About

Medications

Latest Posts

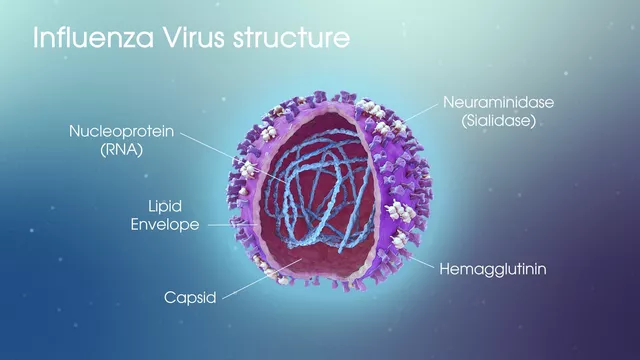

The science behind reemerging influenza: understanding virus mutations

By Orion Kingsworth May 15, 2023

Womenra (Sildenafil) vs Viagra, Cialis & Other ED Drugs - 2025 Comparison Guide

By Orion Kingsworth Oct 12, 2025

Abiraterone: Transforming Prostate Cancer Care for African American Men

By Orion Kingsworth Oct 18, 2025