The prescription drug prices in the United States are among the highest in the world. For instance, Americans with Wilson's disease pay over $88,000 a year for Galzin, while the same medication costs just $1,400 in the UK. This isn't an isolated case-U.S. patients routinely pay three times more than people in other developed nations for identical drugs. What makes this system so expensive?

How Government Policies Shape Drug Costs

One major reason is the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 is a law that specifically prohibited Medicare from negotiating drug prices directly with manufacturers, creating a structural disadvantage that has persisted for over 20 years.. Before this law, Medicare could negotiate bulk discounts for seniors. Now, it can't. Meanwhile, countries like Germany and Canada use government negotiation to keep prices low. In fact, the White House confirmed in November 2025 that Americans pay more than three times what other OECD nations pay for brand-name drugs.

This lack of negotiation power affects millions. For example, when Medicare covers a drug like Ozempic for diabetes, it pays whatever the manufacturer sets. There's no leverage to push for lower costs. Senator Bernie Sanders' September 2025 report showed 688 drugs increased in price after President Trump took office, despite promises to lower costs. The system is designed to let drugmakers set prices freely, with little oversight.

The Role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) are third-party administrators that negotiate drug prices between manufacturers and insurers, but their role has evolved to include vertical integration that often increases costs.. Originally meant to save money by bulk-buying discounts, PBMs now operate as giant middlemen with conflicting incentives. They earn more when list prices are high because they take a percentage of rebates. A Morgan Lewis April 2025 analysis found PBMs control 80% of prescription drug transactions in the U.S., yet their operations are opaque. Patients rarely see the discounts they negotiate-instead, those savings often go to insurers or PBMs themselves.

Consider how PBMs work: a drug manufacturer sets a high list price (say $1,000 for a medication), then offers a rebate to the PBM. The PBM keeps part of that rebate, while the patient still pays the full $1,000 at the pharmacy. This creates a cycle where higher list prices mean bigger rebates for PBMs, even if patients pay more out of pocket. The HHS announced new transparency rules in September 2025 to address this, but progress has been slow.

International Price Comparisons

| Drug Name | U.S. Price | UK Price | Germany Price | Markup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galzin | $88,800/year | $1,400/year | $2,800/year | 1,555% |

| Ozempic | $1,000/month | $350/month | $350/month | 186% |

| Wegovy | $1,350/month | $350/month | $350/month | 286% |

| Humira | $7,000/month | $1,500/month | $1,800/month | 367% |

These numbers aren't random. IQVIA Institute reported U.S. drug prices grew 11.4% in 2024, up from 4.9% in 2023. Specialty drugs like those for diabetes and obesity are driving this surge. The same pill made in the same factory costs vastly more in the U.S. because other countries have price controls. Germany uses reference pricing, comparing costs across similar drugs. Canada negotiates directly with manufacturers. The U.S. has no such system.

Recent Reforms and Their Limits

The Inflation Reduction Act is a law that allows Medicare to negotiate prices for some drugs and requires drugmakers to pay rebates if prices rise faster than inflation.. Starting in 2026, Medicare will negotiate prices for 10 drugs, saving $1.5 billion in out-of-pocket costs. The White House announced deals lowering Ozempic to $350/month and Wegovy to $350/month-down from $1,000 and $1,350-but these are exceptions, not systemic change.

However, the 2025 budget reconciliation bill (HR 1) weakened these provisions, according to KFF analysis. Medicare spending increased by at least $5 billion because of it. CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure called the $2,000 annual out-of-pocket cap for Medicare drugs "life-changing," but critics say it's too little, too late. For example, the American Progress report warns Project 2025's prescription drug plan would raise costs for 18.5 million seniors. Meanwhile, IQVIA predicts specialty drugs will keep driving spending growth of 9.0-11.0% in 2025.

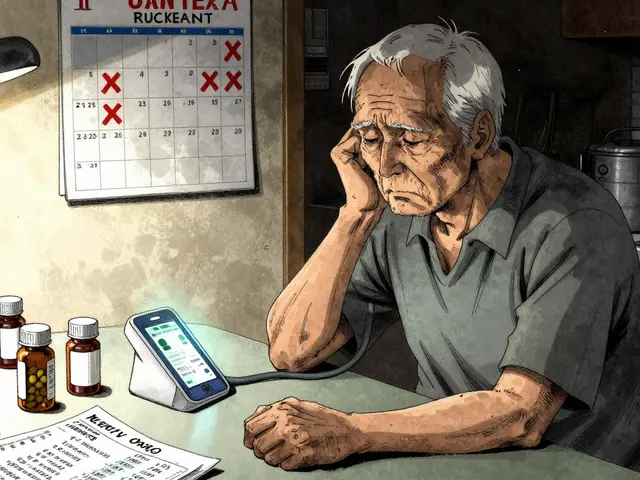

Real-Life Impact on Patients

For many Americans, high drug prices mean impossible choices. A 62-year-old diabetic might skip insulin doses to afford rent. A cancer patient might ration chemotherapy. The Medicare Rights Center's October 2025 report found patients face "difficult choices between paying for prescriptions and other basic needs." Senator Sanders documented cases where people pay $88,000 for Galzin while others in the UK pay $1,400 for the same treatment. These aren't hypotheticals-they're daily realities for 1.5 million Medicare beneficiaries with high out-of-pocket costs.

Even when drugs are affordable, the system creates confusion. A patient might see a $50 co-pay at the pharmacy, only to get a bill later for hundreds more. This happens because PBMs and insurers don't share real-time pricing. The HHS transparency rule aims to fix this, but implementation is slow. For now, patients often don't know what they'll pay until after they fill a prescription.

Why Fixing This Is So Hard

Reform faces massive hurdles. Pharmaceutical companies spend billions lobbying Congress. The White House's May 2025 Executive Order "Delivering Most-Favored-Nation Prescription Drug Pricing" tried to align U.S. prices with other nations, but Senator Sanders' report showed 87 drugs increased prices by 8% after Trump sent letters to manufacturers in July 2025. Legal challenges also block change-drugmakers sue whenever governments try to negotiate prices.

Complexity is another barrier. PBMs, insurers, manufacturers, and pharmacies all have different incentives. A single drug might pass through 5-7 intermediaries before reaching a patient. Each adds costs. The Morgan Lewis analysis calls this "a market power and its impact on consumers" problem. Meanwhile, patent laws let drugmakers extend monopolies for decades. A new obesity drug might cost $10,000 a year for 10 years before generics enter the market. In Europe, those generics arrive much sooner.

Why can't Medicare negotiate drug prices?

The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 explicitly banned Medicare from negotiating drug prices. This law was passed during the Bush administration, and it's never been overturned. Unlike VA or Medicaid, which can negotiate, Medicare must pay whatever manufacturers charge. Some lawmakers propose repealing this ban, but pharmaceutical companies fiercely oppose it.

What role do Pharmacy Benefit Managers play in high drug prices?

PBMs act as middlemen between drugmakers, insurers, and pharmacies. They negotiate rebates but keep a portion, often incentivizing higher list prices. For example, if a drug's list price is $1,000 and the PBM gets a 20% rebate ($200), they might pocket $150 while the patient pays the full $1,000. This creates a perverse system where higher prices mean more profit for PBMs, not savings for patients.

How do other countries control drug prices?

Most developed nations use direct government negotiation or reference pricing. Germany compares prices of similar drugs and sets a maximum cost. Canada negotiates bulk deals with manufacturers. The UK's NHS has a strict budget for drugs and rejects ones that don't meet value thresholds. These systems keep prices low-U.S. patients pay 3x more for the same drugs because no such controls exist here.

Has the Inflation Reduction Act lowered drug prices?

Yes, but only for a few drugs. In 2026, Medicare will negotiate prices for 10 drugs, saving $1.5 billion in out-of-pocket costs. The White House also secured deals lowering Ozempic to $350/month and Wegovy to $350/month. However, these changes affect less than 1% of all prescription drugs. The 2025 budget reconciliation bill weakened the law's scope, so broader impact is limited.

What can be done to reduce drug costs?

Experts suggest several fixes: repealing the Medicare negotiation ban, capping out-of-pocket costs for all patients, requiring PBMs to pass rebates to consumers, and adopting international reference pricing. Senator Sanders' Prescription Drug Price Relief Act would tie U.S. prices to those in other developed nations. However, pharmaceutical lobbying has blocked most reforms. Real change would require political will to prioritize patients over industry profits.

Ashley Hutchins

February 7, 2026 at 22:40

people like me who work hard dont deserve to pay 88k for a pill that costs 1400 in uk

its just wrong

drug companies are greedy and the government lets them get away with it

why cant we just negotiate like other countries

its not rocket science

this system is broken

someone needs to do something about it

i dont care what the politicians say

theyre all in the pocket of big pharma

its disgusting