Have you ever filled a prescription and been shocked by the price? Maybe you’ve seen a drug like EpiPen, Spiriva, or Gleevec listed at hundreds or even thousands of dollars per month - and then wondered why there’s no cheaper version available. It’s not because no one tried to make one. It’s because the system is designed to stop them.

Patents aren’t the only barrier

Most people think generic drugs show up right after a brand-name drug’s patent runs out. That’s not true. Patents are just the starting line. A typical drug patent lasts 20 years from the date it’s filed, but that clock starts ticking long before the drug even hits shelves. By the time the FDA approves it, maybe five or six years have already passed. That leaves maybe 14 years of market exclusivity - not enough to recoup the $2.6 billion average cost of developing a new drug, according to Tufts University.

So companies don’t just rely on one patent. They build patent thickets - dozens of overlapping patents covering everything from the chemical formula to the pill coating, the delivery device, even the way it’s taken. One company might patent the active ingredient, then file another for the tablet’s shape, another for the time-release mechanism, and another for how it’s packaged. Each one can add months or years of extra protection. That’s how Nexium stayed alone for over a decade after its original patent expired.

Complex drugs can’t be copied

Not all drugs are made the same. Some are simple molecules - like atorvastatin, the active ingredient in Lipitor. Those are easy to copy. Once the patent expired, dozens of manufacturers made generics, and the price dropped 85%.

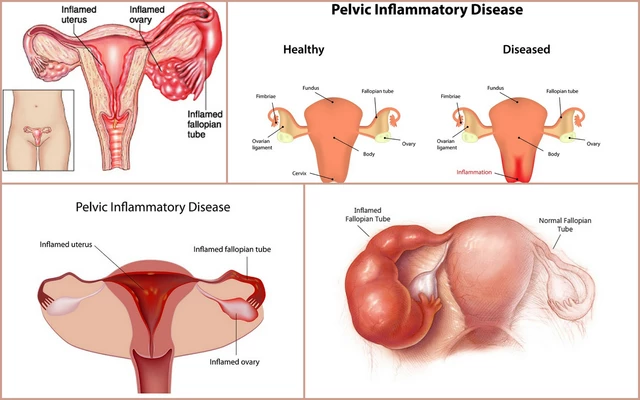

But what about drugs like Premarin? It’s made from the urine of pregnant mares. It contains 10 or more different estrogen compounds, and scientists still don’t fully understand which ones do what. You can’t replicate that in a lab. No generic version exists - even though the patent expired decades ago.

Same goes for inhalers like Advair or Spiriva. The active ingredient might be simple, but the device that delivers it? That’s where the real innovation (and protection) lies. The exact pressure, particle size, and nozzle design affect how well the drug gets into your lungs. Generic makers have to prove their version works the same - and the FDA requires full clinical trials for that. It’s expensive. It’s slow. Many companies just give up.

Biologics: The next frontier

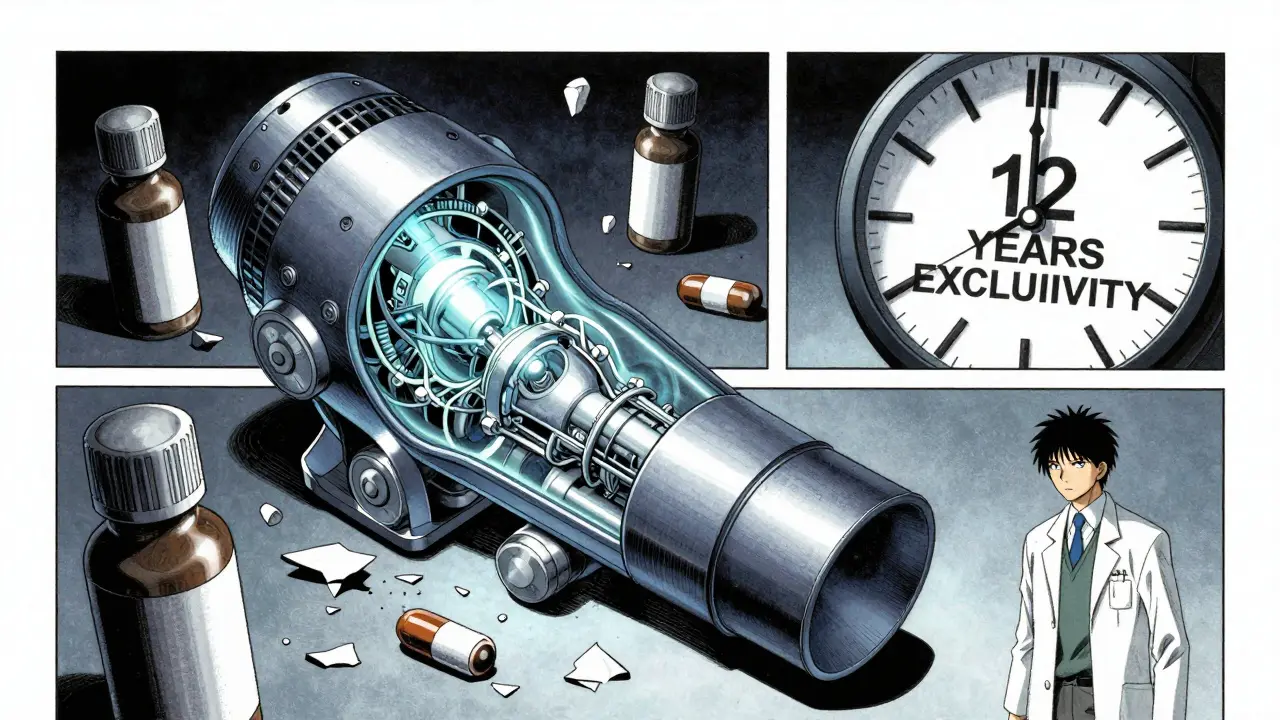

Biologic drugs - like Humira, Enbrel, or insulin - are made from living cells. Not chemicals. Cells. That means every batch is slightly different. You can’t just mix the same ingredients in a vat and call it the same drug. That’s why the FDA created a whole new category: biosimilars.

But biosimilars aren’t generics. They’re more like close cousins. They require 12 years of exclusivity before even being considered. And even then, they need massive clinical studies to prove they’re safe and effective. The first Humira biosimilar didn’t reach the U.S. until 2023 - seven years after its patent expired. Why? Because the manufacturer sued every potential competitor into submission. Patent litigation can drag on for years.

Manufacturing is a minefield

Even if a drug isn’t complex, making a generic version isn’t plug-and-play. The FDA requires generics to be bioequivalent - meaning they must deliver the same amount of drug into your bloodstream within 80% to 125% of the brand’s performance. Sounds easy? It’s not.

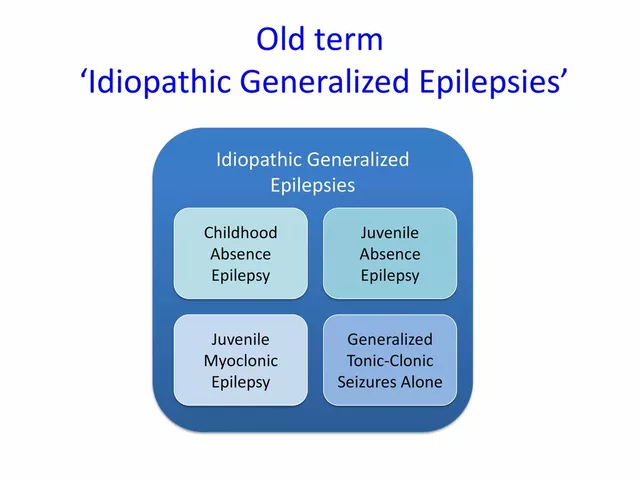

Take a once-a-week version of Prozac. The extended-release coating has to dissolve slowly over days. Change the binder, the filler, the coating thickness - even slightly - and the drug releases too fast or too slow. That could mean side effects, or worse, no effect at all. For drugs with narrow therapeutic windows - like epilepsy meds or thyroid pills - that’s dangerous. The FDA demands extra testing. That costs $5 million to $10 million per product. Many generic makers just don’t see the return.

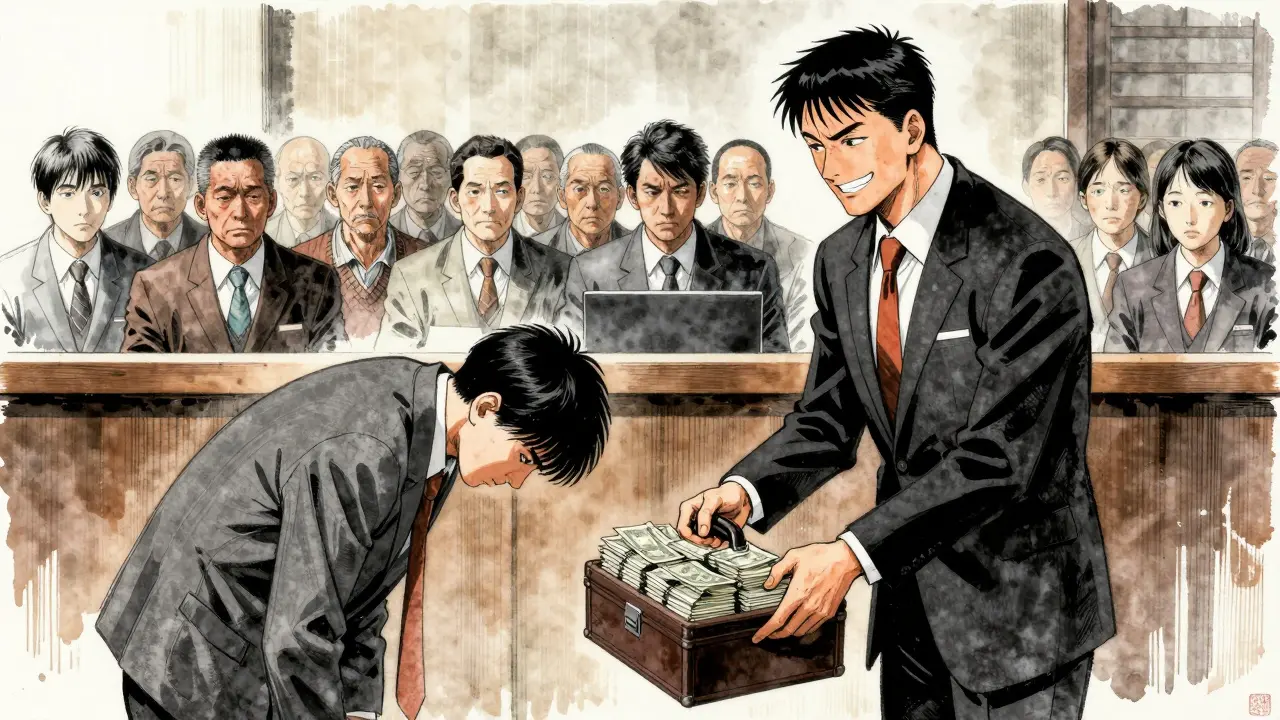

Pay-for-delay and product hopping

Here’s where things get shady. Some brand-name companies don’t wait for patents to expire. They pay generic makers to stay away. It’s called pay-for-delay. The FTC found 297 of these deals between 1999 and 2012. In one case, a brand-name company paid a generic maker $100 million to delay launching a cheaper version for 18 months. That’s not innovation. That’s a bribe.

Then there’s product hopping. Just before a patent runs out, the company releases a slightly modified version - maybe a new pill shape, a new delivery method, or a new flavor. It’s not better. It’s not safer. But the FDA treats it as a new product. So the clock resets. Patients are pushed to the new version, and the old one loses its generic eligibility. This tactic has delayed generics for an estimated 12 to 18 months per drug.

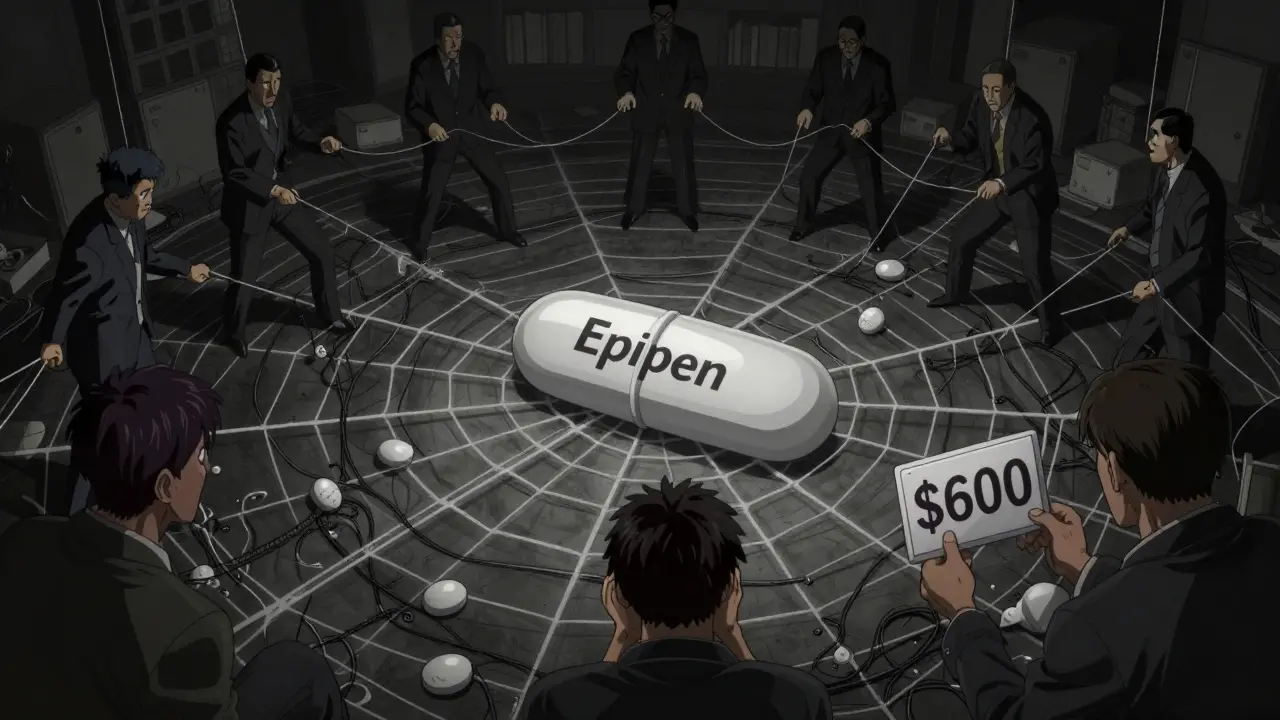

The cost of no competition

When a drug has no generic, it costs 30% to 60% more on average. For some, it’s worse. GoodRx found that brand-name drugs with no generic alternatives cost 437% more than drugs with generics. EpiPen, for example, cost $600 for a two-pack in 2015 - even though the active ingredient, epinephrine, has been around since the 1900s. Mylan didn’t invent it. They just controlled the delivery device and kept the patent alive.

Patients pay the price. Medicare beneficiaries on drugs without generics spend over $5,000 a year out-of-pocket - more than double those on generics. In Australia, where drug pricing is regulated, these disparities are smaller. But in the U.S., it’s a financial burden that forces people to skip doses, split pills, or go without.

What’s changing?

There’s some hope. The CREATES Act of 2019 stopped brand-name companies from blocking generic makers from getting samples of their drugs - a tactic they used to delay testing. The FDA’s 2022 Generic Drug User Fee Amendments sped up reviews of complex generics. And biosimilar approvals are rising - from 32 in 2022 to an expected 75 by 2025.

But the truth is, about 5% of drugs will likely never have true generics. These are ultra-complex biologics, orphan drugs for rare diseases, and products with delivery systems too intricate to copy. For those, biosimilars are the best we can do - and they’re still expensive.

What can you do?

If you’re on a drug with no generic:

- Ask your doctor if there’s a therapeutically equivalent drug - one that works the same way but has a generic. For example, switching from Viibryd to sertraline can save thousands.

- Check the FDA’s Orange Book. It lists patents and exclusivity dates. You might be surprised to learn the patent expired years ago - and the company is just dragging out litigation.

- Use pharmacy discount cards. GoodRx, SingleCare, and others often have prices lower than insurance co-pays.

- Advocate. Contact your representatives. The system isn’t broken - it was built this way.

Generics aren’t magic. They’re competition. And competition drives down prices. When it’s blocked, patients suffer. The next time you see a drug priced like a luxury item, ask: Why? And who’s stopping the cheaper version from arriving?