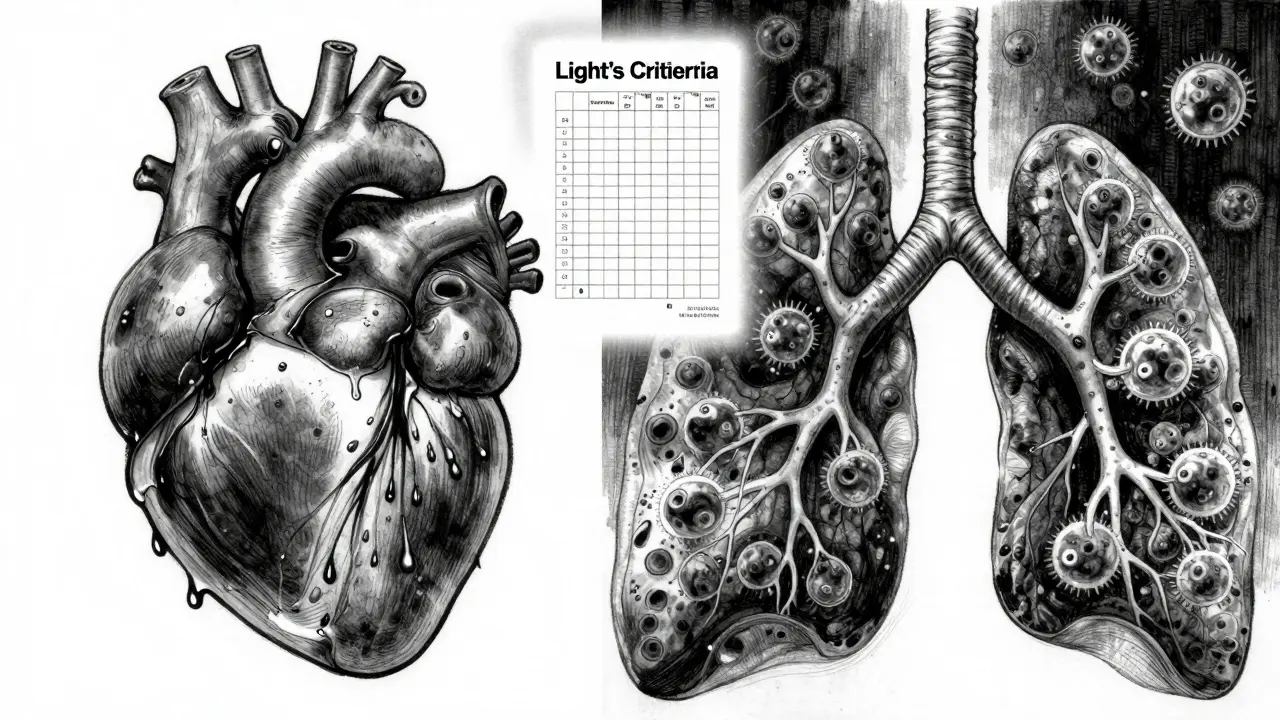

When fluid builds up around your lungs, it doesn’t just make you breathe harder-it can be a sign of something serious. This buildup, called pleural effusion, happens when too much fluid leaks into the space between your lungs and chest wall. It’s not a disease on its own, but a symptom. And if left unchecked, it can lead to severe breathing problems, infections, or even worsen an underlying condition like cancer or heart failure.

What Causes Pleural Effusion?

Not all pleural effusions are the same. They’re split into two main types: transudative and exudative. The difference matters because it tells you what’s going on inside your body.Transudative effusions happen when pressure or protein levels in your blood get out of balance. The most common cause? Congestive heart failure. About half of all pleural effusions come from this. When your heart can’t pump well, fluid backs up into your lungs and chest space. Other causes include liver cirrhosis-where your liver stops making enough protein-and nephrotic syndrome, where your kidneys leak protein into your urine. These are systemic issues, not local infections.

Exudative effusions are different. They’re caused by inflammation, infection, or cancer. Pneumonia is the biggest culprit, responsible for 40-50% of these cases. When lungs get infected, tiny blood vessels leak fluid and white blood cells into the pleural space. Cancer is next-about 30-40% of exudative effusions come from tumors, especially lung, breast, or lymphoma. Pulmonary embolism and tuberculosis also show up here, though less often.

Here’s the key: if your fluid is exudative, you’re not just dealing with fluid-you’re dealing with a disease that needs treatment. That’s why doctors don’t just drain it and walk away. They test it. And that test starts with thoracentesis.

What Is Thoracentesis and When Is It Done?

Thoracentesis is the procedure used to remove fluid from around the lungs. It’s simple, quick, and done under local anesthesia. But it’s not for every case.Doctors only do it if the fluid is more than 10mm thick on an ultrasound. If you’re not short of breath and the fluid is tiny, they’ll watch you instead. Unnecessary thoracentesis doesn’t help-it just adds risk.

During the procedure, a thin needle or catheter is inserted between your ribs, usually near the 5th to 7th space on your side. Ultrasound guides the needle in real time. This isn’t optional anymore. Before ultrasound became standard, complications like collapsed lungs happened in nearly 19% of cases. Now? That number dropped to 4.1%. That’s an 80% reduction in risk.

For diagnosis, they take 50-100 mL of fluid. For relief, they can safely remove up to 1,500 mL in one session. But they don’t just drain and go. The fluid gets tested for:

- Protein and LDH levels (to tell transudate from exudate using Light’s criteria)

- Pleural fluid pH (below 7.2 means infection is spreading)

- Glucose (low levels suggest empyema or rheumatoid arthritis)

- Cell count (to spot infection or cancer cells)

- Cytology (to find cancer cells-successful in 60% of malignant cases)

Some labs also check amylase (for pancreatitis-related fluid) or hematocrit (if it’s over 1%, it could mean a pulmonary embolism). These details turn a simple drain into a diagnostic tool.

What Are the Risks of Thoracentesis?

It’s generally safe, but not risk-free. About 10-30% of people have some kind of complication. The most common? Pneumothorax-a collapsed lung. It happens in 6-30% of cases without ultrasound, but drops to under 5% when guided.Another rare but dangerous risk is re-expansion pulmonary edema. This happens when the lung refills with fluid too fast after being collapsed for days. It’s rare-only 0.5-1% of cases-but can be life-threatening. That’s why doctors don’t drain more than 1,500 mL at once unless they’re monitoring closely.

Hemorrhage (bleeding) occurs in 1-2% of cases, especially if you’re on blood thinners. That’s why doctors check your clotting status before the procedure.

The biggest mistake? Doing thoracentesis without testing the fluid. Studies show 30% of procedures on small, asymptomatic effusions provide no benefit. And 25% of effusions later found to be cancerous were missed because they weren’t tested properly. That’s why the American Thoracic Society says: if it’s bigger than 10mm, test it.

How Do You Prevent Pleural Effusion from Coming Back?

Draining the fluid helps you breathe-but it doesn’t fix the cause. That’s why recurrence is so common. Without treatment, 50% of malignant effusions come back within 30 days.Prevention depends entirely on the root cause.

For cancer-related effusions: The old way was to drain it, then do talc pleurodesis-injecting talc to stick the lung to the chest wall. It works in 70-90% of cases. But it’s painful, requires hospitalization, and often needs a chest tube for days.

The new standard? Indwelling pleural catheters (IPCs). These are small tubes left in place for weeks. You drain the fluid yourself at home, a little at a time. Success rates are 85-90% after six months. Hospital stays drop from 7 days to under 2.5 days. Patients report better quality of life. That’s why major guidelines now recommend IPCs as first-line for malignant effusions.

For heart failure: Drain the fluid? Sure. But the real fix is treating the heart. Diuretics, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers-these reduce recurrence to under 15% within three months. Monitoring NT-pro-BNP levels helps doctors adjust meds before fluid builds up again.

For pneumonia-related effusions: Antibiotics are the main treatment. But if the fluid is thick, infected, or has a pH below 7.2, you need drainage. If you don’t, 30-40% of cases turn into empyema-pus in the chest. That requires surgery.

After heart surgery: About 15-20% of patients get fluid buildup. Most go away on their own. But if you’re draining more than 500 mL per day for three days straight, you need a chest tube. Keep it in for a few days, and recurrence drops to 95%.

Why Treating the Cause Matters More Than Draining

Dr. Richard Light, who created the diagnostic criteria used worldwide today, once said: “Treating the effusion without treating the cause is like bailing water from a sinking boat without patching the hole.”That’s still true. You can drain fluid every week for months. But if your heart keeps failing, your cancer keeps spreading, or your pneumonia doesn’t clear, the fluid will return. Every time.

Modern treatment isn’t about removing fluid-it’s about identifying the cause fast and acting on it. Ultrasound-guided thoracentesis, fluid analysis, and targeted therapies have changed everything. Survival rates for malignant effusions have doubled in the last decade-from 10% to 25% over five years-because we’re treating the cancer, not just the symptom.

And the trend is clear: personalized care works. Tailoring treatment to the type of cancer, the patient’s overall health, and the fluid’s exact chemistry leads to better outcomes. No more one-size-fits-all.

What Should You Do If You Have Pleural Effusion?

If you’re diagnosed with pleural effusion, ask these questions:- Is the fluid transudative or exudative? (This determines the next steps.)

- Was ultrasound used during the drain? (If not, ask why.)

- Was the fluid tested for protein, LDH, pH, glucose, and cytology? (If not, demand it.)

- What’s the underlying cause? (Don’t accept “fluid buildup” as an answer.)

- What’s the plan to prevent it from coming back? (Drainage alone isn’t a plan.)

Don’t settle for temporary relief. Ask for the full picture. Your lungs-and your life-depend on it.

Can pleural effusion go away on its own?

Yes, in some cases. Small effusions from minor infections or after surgery can resolve without treatment. But if it’s linked to heart failure, cancer, or pneumonia, it won’t go away unless the root cause is treated. Never assume it’s harmless just because you feel better after draining.

Is thoracentesis painful?

You’ll feel pressure and a brief pinch when the needle goes in, but local anesthesia prevents sharp pain. Some people feel a pulling sensation as fluid drains, which is normal. Afterward, mild soreness at the site is common but usually fades in a day or two.

How long does it take to recover from thoracentesis?

Most people go home the same day. You’ll be asked to rest for 24 hours and avoid heavy lifting. If you had a large drain or complications like a small pneumothorax, you might need to stay overnight. Full recovery usually takes 1-3 days.

Can pleural effusion be a sign of lung cancer?

Yes. Malignant pleural effusion is a known sign of advanced lung cancer, breast cancer, lymphoma, or other cancers that spread to the chest. Cytology tests on the fluid can detect cancer cells in about 60% of cases. If cancer is suspected, further imaging and biopsy are needed.

What’s the difference between a pleural effusion and a collapsed lung?

A pleural effusion is fluid between the lung and chest wall. A collapsed lung (pneumothorax) is air in that space. They can happen together-especially after thoracentesis-but they’re different. One is fluid, the other is air. Both prevent the lung from expanding fully.

Are there alternatives to thoracentesis for diagnosing pleural effusion?

Imaging like CT scans or chest X-rays can show fluid, but they can’t tell you why it’s there. Only fluid analysis through thoracentesis gives you the cause. That’s why it’s still the gold standard-even with advanced imaging.

Can I prevent pleural effusion from happening?

You can’t always prevent it, but you can reduce your risk. Manage heart failure with meds and diet. Quit smoking to lower lung cancer and pneumonia risk. Get vaccinated for flu and pneumonia. If you’ve had one before, follow up regularly-early detection saves lives.

Josh McEvoy

January 23, 2026 at 19:53

bro i got pleural effusion after a bad cold last year and they just drained it... no tests, no ultrasound, just "you're fine". 10 days later i was back in the ER with pneumonia. 🤦♂️