B12 Treatment Pathway Calculator

Determine Your B12 Treatment Pathway

This tool helps identify the most appropriate B12 treatment route based on your symptoms and medical history. Based on guidelines from the article.

Atrophic gastroenteritis is a chronic inflammation that thins the lining of the stomach, often leading to a drop in intrinsic factor and, consequently, vitamin B12 deficiency. If you’ve been diagnosed with either condition, understanding how they intertwine, what symptoms to watch for, and which treatments work best can change the course of your health.

What Exactly Is Atrophic Gastroenteritis?

Atrophic gastroenteritis, sometimes called chronic atrophic gastritis, is an immune‑mediated or Helicobacter pylori‑related degeneration of the gastric mucosa. The disease slowly destroys the secretory cells that produce acid and intrinsic factor (IF), a protein essential for absorbing cobalamin (vitamin B12) in the ileum.

Key characteristics:

- Loss of parietal cells (the acid‑producing cells)

- Reduced secretion of intrinsic factor

- Thickened, pale‑looking stomach lining on endoscopy

When parietal cells dwindle, the stomach’s acidic environment weakens, and the body can’t capture dietary B12 effectively, setting the stage for deficiency.

How Vitamin B12 Deficiency Develops

Vitamin B12, or cobalamin, travels from food to the bloodstream only after binding to intrinsic factor in the duodenum. Without enough IF, B12 remains in the gut and is expelled.

Deficiency typically shows up years after the atrophic changes begin because the liver stores up to 3 grams of B12-enough for 3‑4 years of normal use. When stores are exhausted, the following issues arise:

- Impaired DNA synthesis → megaloblastic anemia

- Neurological damage → peripheral neuropathy, gait disturbances, memory lapses

- Psychiatric symptoms → depression, irritability, even psychosis in severe cases

Recognizing the Signs

Symptoms can be subtle at first, then progress quickly once anemia or neuro‑issues appear. Common clues include:

- Fatigue and weakness despite adequate sleep

- Pale skin, shortness of breath on mild exertion

- Tongue that looks smooth, beefy, or sore (glossitis)

- Numbness or tingling in hands and feet

- Difficulty walking, frequent stumbling

- Memory fog, mood swings, or unexplained depression

Because these signs overlap with many other conditions, a proper work‑up is essential.

Diagnostic Pathway

Doctors combine blood tests, imaging, and sometimes functional studies to confirm both atrophic gastroenteritis and B12 deficiency.

| Test | Purpose | Typical Findings in Atrophic Gastroenteritis + B12 Deficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Serum B12 level | Quantify circulating cobalamin | Below 200 pg/mL (often <150 pg/mL) |

| Methylmalonic acid (MMA) | Sensitive marker for cellular B12 deficiency | Elevated MMA despite normal B12 in early stages |

| Homocysteine | Another functional B12 marker | Elevated, paralleling MMA |

| Complete blood count (CBC) | Detect megaloblastic anemia | Macro‑ovalocytes, low hemoglobin, high MCV (>100 fL) |

| Anti‑parietal cell antibodies | Identify autoimmune component | Positive in up to 90% of autoimmune cases |

| Anti‑intrinsic factor antibodies | Specific for pernicious anemia | Positive in ~50‑70% of cases |

| Gastroscopy with biopsy | Visualize and confirm mucosal thinning | Atrophic mucosa, intestinal metaplasia, loss of chief cells |

In rare situations where oral absorption is questionable, the Schilling test (historical) can differentiate malabsorption from dietary lack, though most labs now rely on MMA and antibody panels.

Treatment Options: Restoring B12 Levels

Once deficiency is confirmed, replenishing B12 is the priority. Two main routes exist:

| Route | Dosage Regimen | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral cyanocobalamin or methylcobalamin | 1,000‑2,000 µg daily for 1‑2 weeks, then 1,000 µg weekly | Convenient, cheap, self‑administered | Requires intact absorption; may be slower to correct neuro symptoms |

| Intramuscular (IM) injection | 1000 µg IM weekly for 4‑6 weeks, then monthly | Bypasses GI tract, rapid rise in serum B12, reliable for severe neuro deficits | Invasive, requires clinic visits, slightly higher cost |

Most guidelines suggest starting with IM injections for patients with neurological involvement or proven malabsorption, then transitioning to high‑dose oral if they tolerate it.

Addressing the Underlying Gastritis

Reversing atrophic changes is challenging because the loss of parietal cells is often permanent. However, managing contributing factors can halt progression:

- Helicobacter pylori eradication: Triple‑therapy (clarithromycin, amoxicillin, proton‑pump inhibitor) for 14 days reduces inflammation in infection‑driven cases.

- Proton‑pump inhibitors (PPIs) should be used sparingly; chronic overuse may exacerbate atrophy.

- Autoimmune gastritis has no cure; regular B12 monitoring is essential.

- Dietary adjustments-avoid excessive alcohol, smoking, and highly processed foods that irritate the stomach lining.

Periodic endoscopic surveillance is advised for patients with intestinal metaplasia, as they have a modestly increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma.

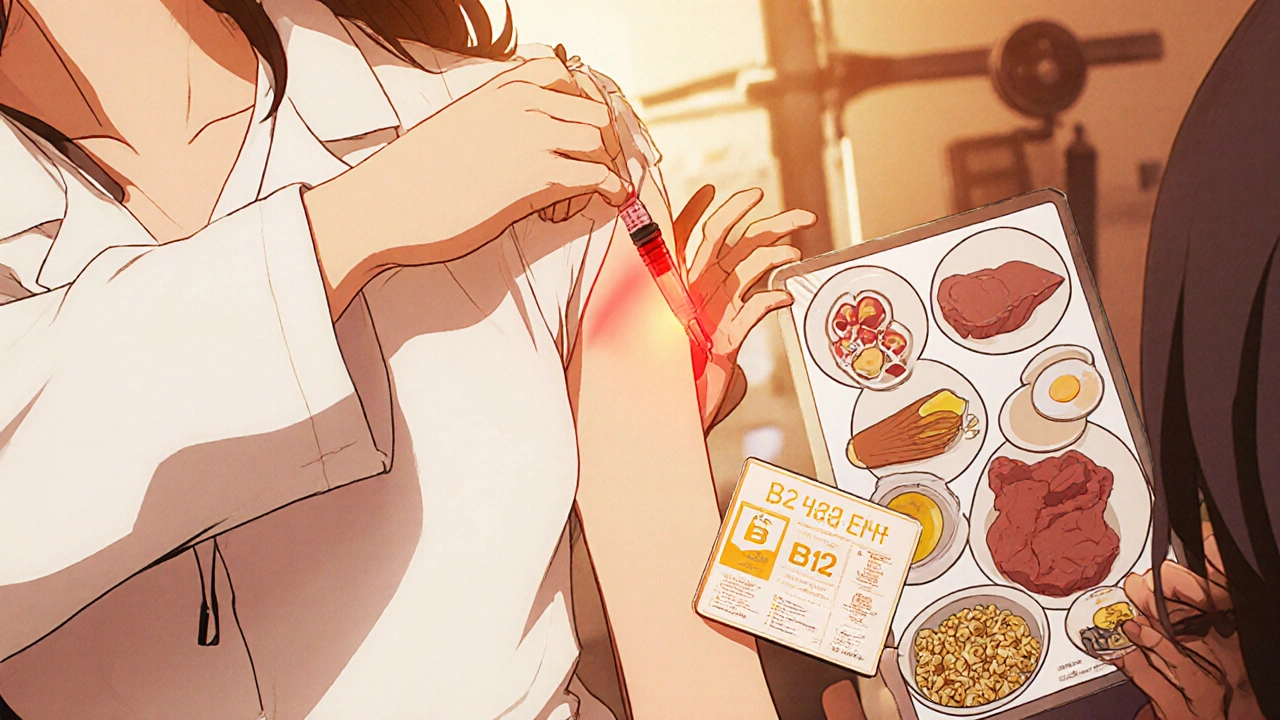

Nutrition: Foods Rich in Vitamin B12

While supplementation is mandatory, a B12‑rich diet supports maintenance:

- Animal liver (especially beef) - up to 70 µg per 100 g

- Clams, oysters, and mussels - 20‑30 µg per 100 g

- Egg yolk - 2.5 µg per large egg

- Low‑fat dairy (milk, yogurt, cheese) - 1‑1.5 µg per cup

- Fortified cereals and plant milks - typically 2‑6 µg per serving

Vegetarians and vegans should rely on fortified products or a reliable supplement because natural plant foods contain negligible B12.

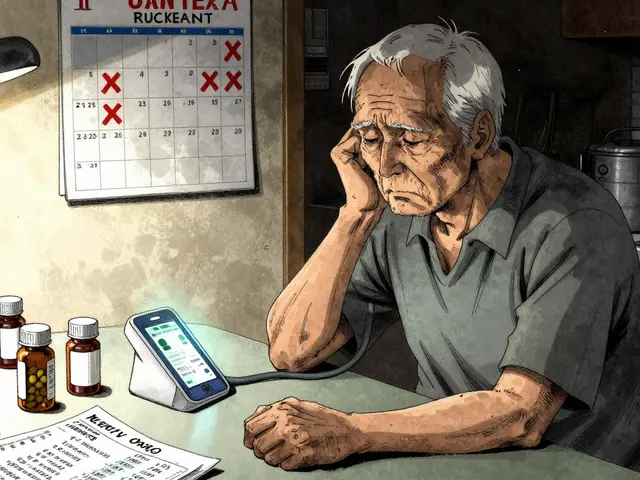

Monitoring and Long‑Term Follow‑Up

After initiating therapy, labs are checked at 2‑3 months to confirm normalization of B12, MMA, and homocysteine. Once stable, annual monitoring suffice unless new symptoms appear.

- Serum B12 should stay >300 pg/mL.

- Repeat CBC to ensure anemia resolves.

- Neurological exam annually; persistent deficits may need extended IM therapy.

Patients with autoimmune gastritis often develop other autoimmune disorders (thyroiditis, type‑1 diabetes). A yearly screen for thyroid‑stimulating hormone (TSH) and blood glucose can catch co‑morbidities early.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even with clear guidelines, mistakes happen:

- Assuming normal serum B12 rules out deficiency - functional markers (MMA, homocysteine) catch early cases.

- Relying only on oral supplements when absorption is compromised - switch to IM if symptoms persist after 2 weeks.

- Stopping B12 therapy after the first normal lab - lifelong maintenance is usually required.

- Neglecting gastric cancer surveillance in metaplastic patients - schedule endoscopy every 3‑5 years.

Key Takeaways

- Atrophic gastroenteritis destroys intrinsic factor, leading to vitamin B12 deficiency and potentially severe anemia or neurological damage.

- Diagnosis combines serum B12, MMA, antibody panels, and gastroscopy.

- High‑dose oral B12 works for many, but injectable therapy is the safest route for severe or malabsorptive cases.

- Treat the root cause - eradicate H. pylori, limit unnecessary acid‑suppressing drugs, and monitor for gastric cancer.

- Life‑long B12 supplementation and regular lab checks are essential to keep symptoms at bay.

Can a vegetarian diet cause B12 deficiency without atrophic gastroenteritis?

Yes. Plant‑based diets lack natural B12, so vegans must rely on fortified foods or supplements. The deficiency mechanism differs - it’s dietary, not malabsorptive, but the clinical picture (megaloblastic anemia, neuropathy) is the same.

How long does it take for neurological symptoms to improve after B12 therapy?

Peripheral neuropathy often begins to improve within weeks of adequate B12 replacement, but full recovery may take months. Severe spinal cord involvement (subacute combined degeneration) can be irreversible if treatment is delayed.

Is the Schilling test still used to diagnose B12 malabsorption?

The Schilling test has largely been replaced by serum MMA, homocysteine, and antibody testing because it’s cumbersome and involves radioactive tracers. It’s reserved for research settings only.

Can proton‑pump inhibitors (PPIs) cause B12 deficiency?

Long‑term PPI use reduces stomach acidity, which can impair B12 release from food. This effect is modest but adds to risk in patients already prone to malabsorption, so periodic B12 checks are wise for chronic PPI users.

Do I need to take B12 supplements forever?

Most people with atrophic gastroenteritis have permanent loss of intrinsic factor, so lifelong supplementation is recommended. Your doctor will tailor the dose and route based on symptom control and lab results.

Ritik Chaurasia

October 22, 2025 at 12:44

Listen up, folks – if you’re ignoring the link between atrophic gastroenteritis and B12 deficiency, you’re basically signing a death warrant for your nerves and blood. In India we’ve seen generations suffer from hidden anemia because the diet lacks enough meat, and the autoimmune gastritis just makes it worse. Stop blaming “just getting older” and start getting checked; the blood test, the antibody panel, the endoscopy – they’re not optional. Pump that B12 in, either oral mega‑doses or injections, and watch the fatigue melt away.

Don’t let a PPI prescription become a permanent habit, or you’ll be digging your own grave faster.