When you pick up a pill, you’re probably thinking about the active ingredient-the drug that treats your condition. But what you’re holding is mostly excipients. These are the non-active components: fillers, binders, coatings, flavors, preservatives. They make up 60% to 99% of the tablet’s weight. For decades, regulators and manufacturers called them ‘inactive’-as if they were harmless bystanders. But new science is changing that view. Excipients aren’t just inert filler. Some can directly affect how a drug works-or even cause side effects.

What Are Excipients, Really?

Excipients are everything in a medicine that isn’t the active pharmaceutical ingredient. Common ones include lactose (a milk sugar used as a filler), microcrystalline cellulose (a binder), magnesium stearate (a lubricant), and sodium benzoate (a preservative). The U.S. FDA lists over 1,500 approved excipients across all drug forms-oral pills, injections, eye drops, even inhalers. Each drug typically uses 5 to 15 of them.

They serve real, necessary functions. Without a disintegrant like croscarmellose sodium, a pill wouldn’t break down in your stomach. Without a coating, some drugs would dissolve too fast-or too slow. Without flavoring, liquid antibiotics would be nearly impossible for kids to take. But here’s the problem: calling them ‘inactive’ suggests they’re biologically silent. That’s outdated.

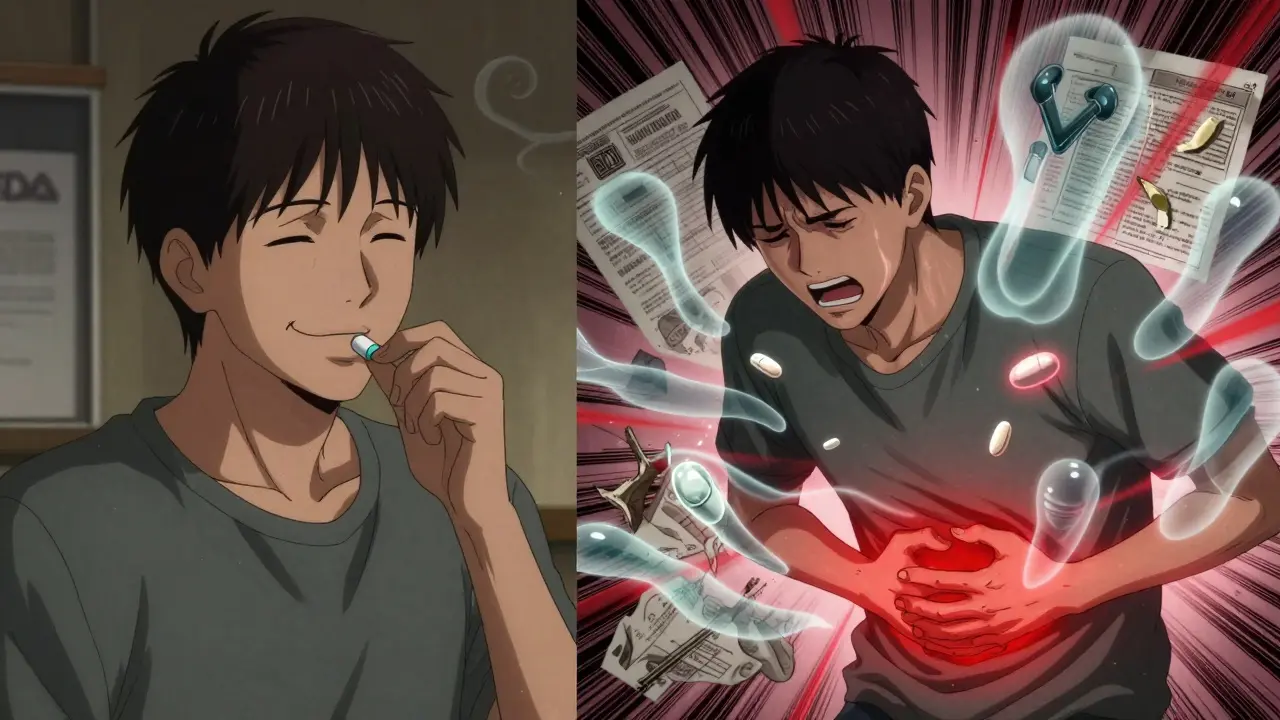

When ‘Inactive’ Isn’t Inert

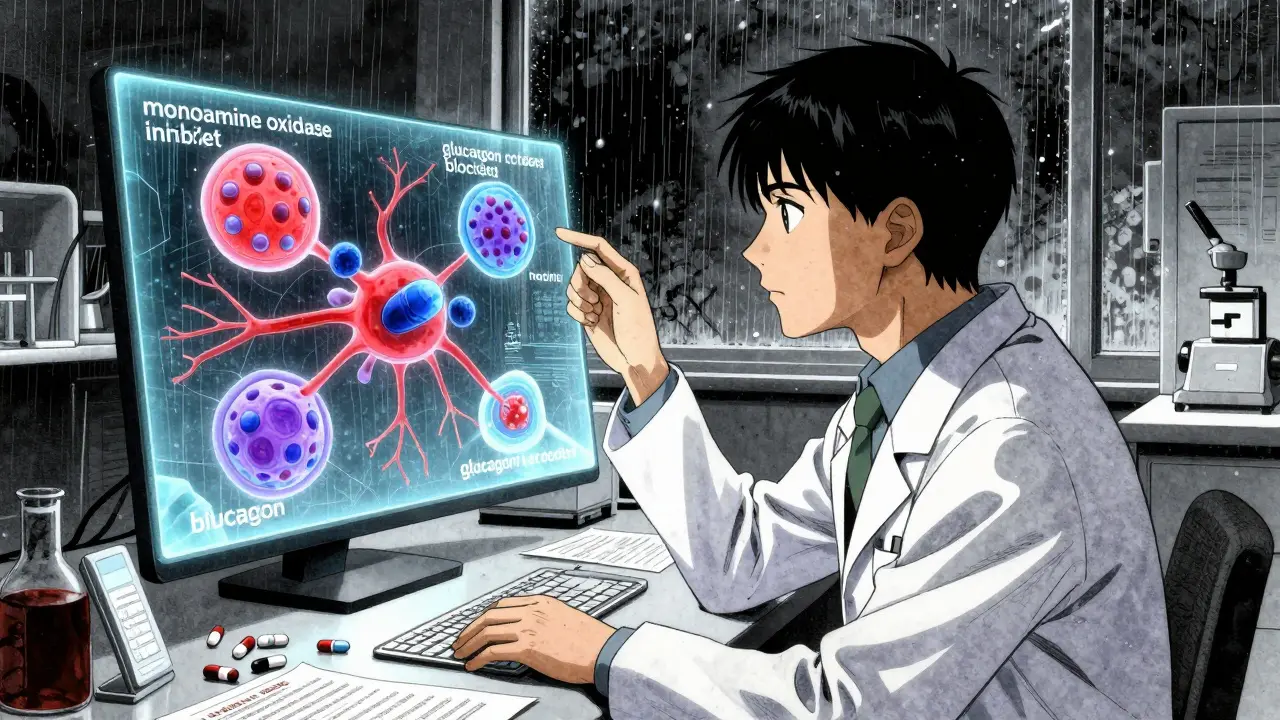

A 2020 study in Science tested 314 excipients against 44 biological targets-and found 38 of them interacted with human cells. Some matched the concentration levels found in your bloodstream after taking a normal dose. That’s not a fluke. It’s biology.

Take aspartame, the artificial sweetener used in some chewable tablets. It blocked the glucagon receptor at just 8.5 micromolar. That’s a level you can hit after swallowing a single tablet. Sodium benzoate, a preservative in liquid medicines, inhibited monoamine oxidase B at 320 nanomolar-a concentration linked to neurological effects. Propylene glycol, found in many IV fluids and oral suspensions, interfered with monoamine oxidase A at 210 nanomolar. These aren’t theoretical numbers. They’re measurable in real patients.

Dr. Giovanni Traverso, lead author of that study, put it bluntly: ‘The blanket classification of excipients as “inactive” is scientifically inaccurate for a meaningful subset of these compounds.’ The FDA now admits the assumption of inertness ‘may not hold for all compounds at all concentrations.’

Why Generic Drugs Can Be Different

Generic drugs are supposed to be identical to brand-name versions. But they’re not always. The FDA allows different excipients in generics-as long as they don’t change safety or effectiveness. That sounds reasonable. But it’s where things get messy.

For injectables, eye drops, or ear drops, generics must match the original excipients exactly. That’s because these drugs enter the bloodstream directly. But for pills? Manufacturers can swap out fillers, binders, or coatings. And they often do-to cut costs, improve stability, or use more available materials.

That’s fine… until it isn’t. In 2020, Aurobindo tried to launch a generic version of Entresto. They replaced magnesium stearate with sodium stearyl fumarate. The FDA rejected it. Why? In vitro tests showed a 15% difference in how fast the drug released at stomach pH. That could mean lower absorption-and less effectiveness.

And it’s not just about absorption. In 2018, 14 generic versions of valsartan were recalled because a new solvent used in manufacturing created a cancer-causing contaminant, NDMA. The solvent wasn’t the active ingredient. It was an excipient-related process change. That’s how deep this goes.

Who Gets Affected?

Most people won’t notice a difference. But some will. People with allergies, metabolic disorders, or sensitivities are at higher risk.

Lactose intolerance? A pill with 200 mg of lactose as filler might cause bloating or diarrhea. That’s not the drug’s fault-it’s the excipient. People with phenylketonuria (PKU) can’t metabolize phenylalanine. Aspartame in chewable tablets? That’s a problem. Even small amounts matter.

And then there’s the ‘idiosyncratic’ reactions-those weird, unpredictable side effects that don’t show up in clinical trials. Dr. Robert Langer of MIT says we’ve underestimated excipients’ role in these reactions. A patient might react to a generic version of their medication, not because the active ingredient changed, but because the coating or lubricant did.

Regulators Are Catching Up

The FDA’s Inactive Ingredient Database (IID) has been around for years. But it’s just a list. It doesn’t tell you what concentrations are safe in different tissues. That’s changing.

In 2023, the FDA proposed updating the IID to include predicted tissue concentrations for each excipient. Why? Because we now know propylene glycol and diethyl phthalate reach levels in the body that overlap with their biological activity. That’s not theoretical-it’s measurable.

They’re also running a pilot program requiring extra safety data for 12 high-risk excipients in orally disintegrating tablets-like aspartame and saccharin-after reports of rare hypersensitivity reactions. That’s a big deal. It means regulators are starting to treat excipients like potential drug components, not just additives.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) already requires manufacturers to justify excipient changes in their Quality Overall Summary. The FDA is moving that way too. By 2025, an estimated 30% of complex generic applications will need extra excipient safety studies-up from 18% in 2022.

What This Means for You

If you’ve ever switched from a brand-name drug to a generic and noticed a change-more side effects, less effectiveness, or a new reaction-you’re not imagining it. Excipients might be why.

Here’s what you can do:

- Check the pill’s inactive ingredients. They’re listed on the packaging or in the patient information leaflet.

- If you have known allergies (lactose, gluten, dyes), compare ingredients between brand and generic versions.

- Don’t assume generics are identical. If you feel different after switching, talk to your pharmacist. Ask if the excipients changed.

- For chronic conditions-like epilepsy, thyroid disease, or heart failure-stick with the same manufacturer if possible. Small formulation changes can matter.

PhRMA says excipients have decades of safety data. And for common ones like cellulose or stearate, that’s mostly true. But the field is changing fast. New delivery systems-extended-release pills, nasal sprays, transdermal patches-use novel excipients that haven’t been tested in millions of people. That’s where the risk is growing.

The Future of Excipients

The International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council (IPEC) is pushing for ‘presumed inert’ thresholds-concentrations below which an excipient is considered harmless. But researchers argue that’s too simplistic. One person’s safe dose is another’s trigger.

The FDA is building a computational model to predict which excipients might interact with biological targets. That could flag risky combinations before they even reach the market. But it’s expensive. If the proposed rule requiring in vitro screening against 50 high-risk targets passes, it could add $500,000 to $1 million to the cost of developing each new excipient.

For now, the system works for most people. But it’s outdated for the future. As drug delivery gets more complex-personalized doses, smart pills, biologics-the idea that ‘inactive’ means ‘safe’ is no longer enough.

Excipients aren’t just filler. They’re part of the medicine. And if you’re taking medication long-term, you deserve to know what else is in that pill.

Are excipients the same in brand-name and generic drugs?

Not always. For injections, eye drops, or ear drops, generics must match the brand’s excipients exactly. But for pills, tablets, and capsules, manufacturers can use different fillers, binders, or coatings-as long as they prove it doesn’t affect how the drug works or its safety. That’s why some people notice differences after switching generics.

Can excipients cause side effects?

Yes. While rare, excipients like lactose, aspartame, sodium benzoate, and propylene glycol have been linked to reactions in sensitive individuals. Lactose can cause digestive issues in intolerant people. Aspartame can be dangerous for those with PKU. Some excipients also interfere with drug absorption or metabolism, leading to reduced effectiveness or unexpected side effects.

How do I find out what excipients are in my medication?

Check the patient information leaflet that comes with your prescription, or look up the drug on the FDA’s website. You can also ask your pharmacist for the inactive ingredients list. Most pharmacies can print it out or show it on their system.

Should I avoid generics because of excipients?

No-not unless you’ve had a reaction. Most people take generics without issue. But if you notice new side effects, reduced effectiveness, or allergic reactions after switching to a generic, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. It could be the excipients. Keep your current version as a backup until you’re sure.

Are there any excipients I should watch out for?

Yes. Common ones to check include: lactose (if you’re intolerant), aspartame (if you have PKU), tartrazine (a yellow dye linked to hypersensitivity), sodium benzoate (can affect liver enzymes), and propylene glycol (can cause irritation or neurological effects at high doses). Always compare ingredients if you have known sensitivities.

Monica Puglia

January 11, 2026 at 20:53

I had no idea lactose could be in pills 😱 My stomach’s been acting up since I switched generics. Finally makes sense. Thanks for this!